Are police officer numbers actually related to an increase in knife crime?

The UK is currently battling against an epidemic of knife-crime. The latest spat of stabbings saw two deaths after seven attacks in London in a single weekend, and marks the 29th death in the capital this year.

And with knife-crime figures so high, it wasn’t long before people started looking at the dwindling number of officers on the street as an explanation. The UK has seen a reduction of 20,000 in the number of officers on the street in the last seven years, which many see as being to blame for the current knife-crisis.

So, when Theresa May announced that there was no correlation between knife crime and the number of police on the streets, she received heavy backlash.

Mark Burns-Williamson, the chairman of the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners, told the Guardian that cuts to police numbers nationwide and cuts to youth services had created “a toxic mix”.

And the UK’s most senior police officer Cressida Dick argued that the two were in fact linked.

But how bad is the current wave of knife-crime? And can it be linked to the dwindling police numbers?

Read more:

- How the amount of police in Kent has fallen – in numbers

- The suprisingly low number of police officers in Kent

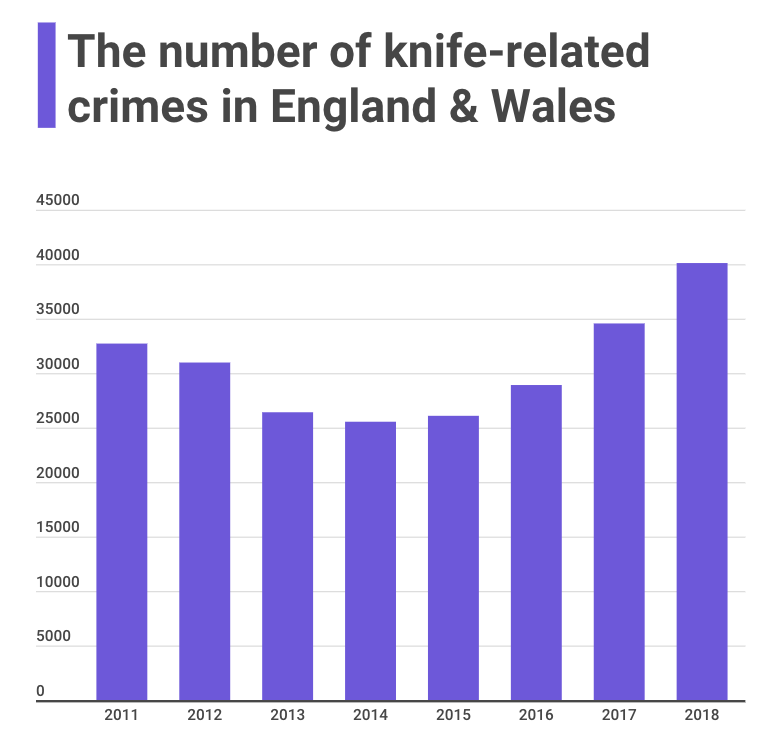

Knife crime – in numbers

The number of violent and sexual crimes involving a knife or sharp instrument in England and Wales has been increasing since the end of 2014, but has seen a particularly dramatic increase in the last two years. The figures have shot up from less than 29,000 in the year ending in April 2016, to over 40,000 in the year ending in April 2018.

And even when you account for the rise in the UK population the number of knife & sharp instrument crimes increases by 36% between April 2016 and March 2018.

Correlation or not?

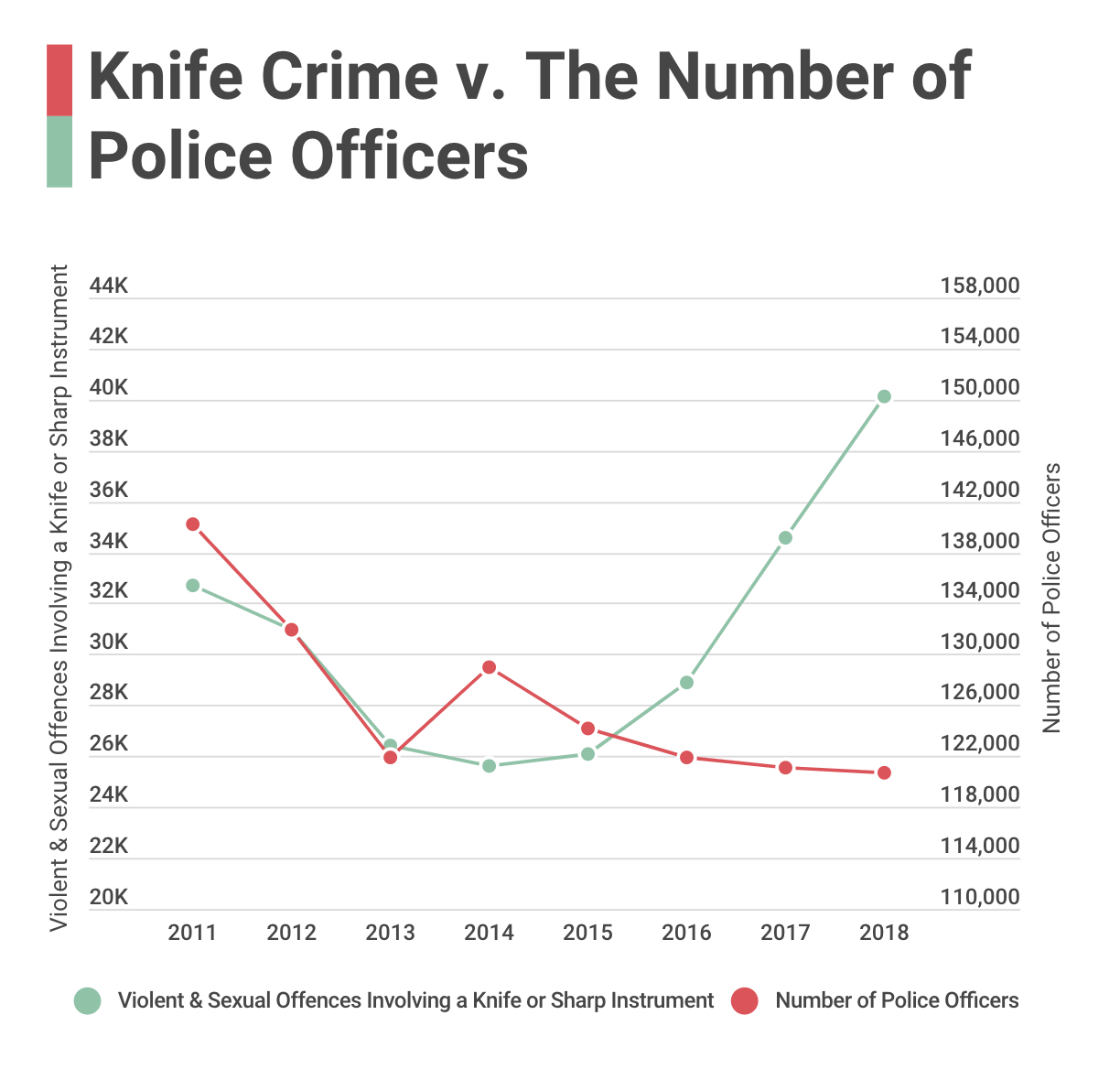

Here’s where things get a bit hazier. The above graph plots the number of knife & sharp instrument crime against the number of police officers.

If the two were perfectly linked, then you would expect the red line to look like an upside-down version of the green line. This would mean that as police numbers fall, knife crime would rise, and vice-versa. Instead we can see that as police numbers dropped by between 2011 and 2013, knife crime actually fell.

That being said, from 2014 onwards the numbers start to look a bit more as expected, with a definite correlation between the two. But if the two were inextricably linked, then they would correlate every time without fail, not just when looking at selective years.

On top of this, the number of police isn’t what we’re actually interested in, it’s the number of officers that are on the streets. And that’s where things get even more complicated, as there is no consensus on how to measure the number of police on the street.

Other factors

Even if falling police numbers do have an effect on the rise in violent crime, it certainly isn’t the only thing to blame. Many look at the closing of youth-related services as having a direct knock-on effect on gang-related crime.

Chief executive of the YMCA Denise Hatton told the Independent that vital services are necessary to provide teenagers with positive activities, help them develop, meet new friends and socialise.

We are condemning young people to become a lonely, lost generation

Denise Hatton, chief executive of the YMCA

“Without drastic action to protect funding and making youth services a statutory service, we are condemning young people to become a lonely, lost generation with nowhere to turn,” she said.

The drop-in stop-searches has also been cited as a possible reason for the increase in violent crimes. Stop-search numbers have drastically dropped in the last 10 years, falling from over 1,400,000 in 2009/10 to less than 400,000 in 2017/18.

But even this isn’t as clear cut as it might seem. A report by the Centre of Crime and Justice Studies found that there was “limited evidence of the effectiveness of stop and search in reducing crime”, according to The Independent.

The report also stated that “It is also recognised as having detrimental effects on certain groups and on community relations with the police. Stop and search is disproportionately used against people of colour, and, after initial improvements, this disproportionality has widened”.