Bengal tigers: How India's big cat is making a comeback

Joe Harbert

Despite tigers being killed every day in the wild, India is determined to prove there can be a future for them on our planet. So why have numbers increased so quickly for the species in their native country, and does bigger trouble still lie ahead for an animal so vital to all of us? Joe Harbert investigates.

As the sun rises over the state of Maharashtra, city metropolises like Mumbai and Nagpur dominate the area’s landscape. High-rise buildings stretch for dozens of miles and exemplify the urbanisation that human activity has created. Populations continue to accelerate rapidly out of control in a part of the world where suburbs now house millions rather than thousands. Jungles and rainforests that once laced this state’s skyline are now all but vacant and out of sight.

Newly built land has highlighted the threat of extinction that this society has inflicted on a host of creatures. The destruction of forests means streets continue to take over what were, for centuries, animal territories. With thousands of species edging closer to an imminent mortal fate, one has gradually been making a comeback, remaining determined not to vanish from the world forever.

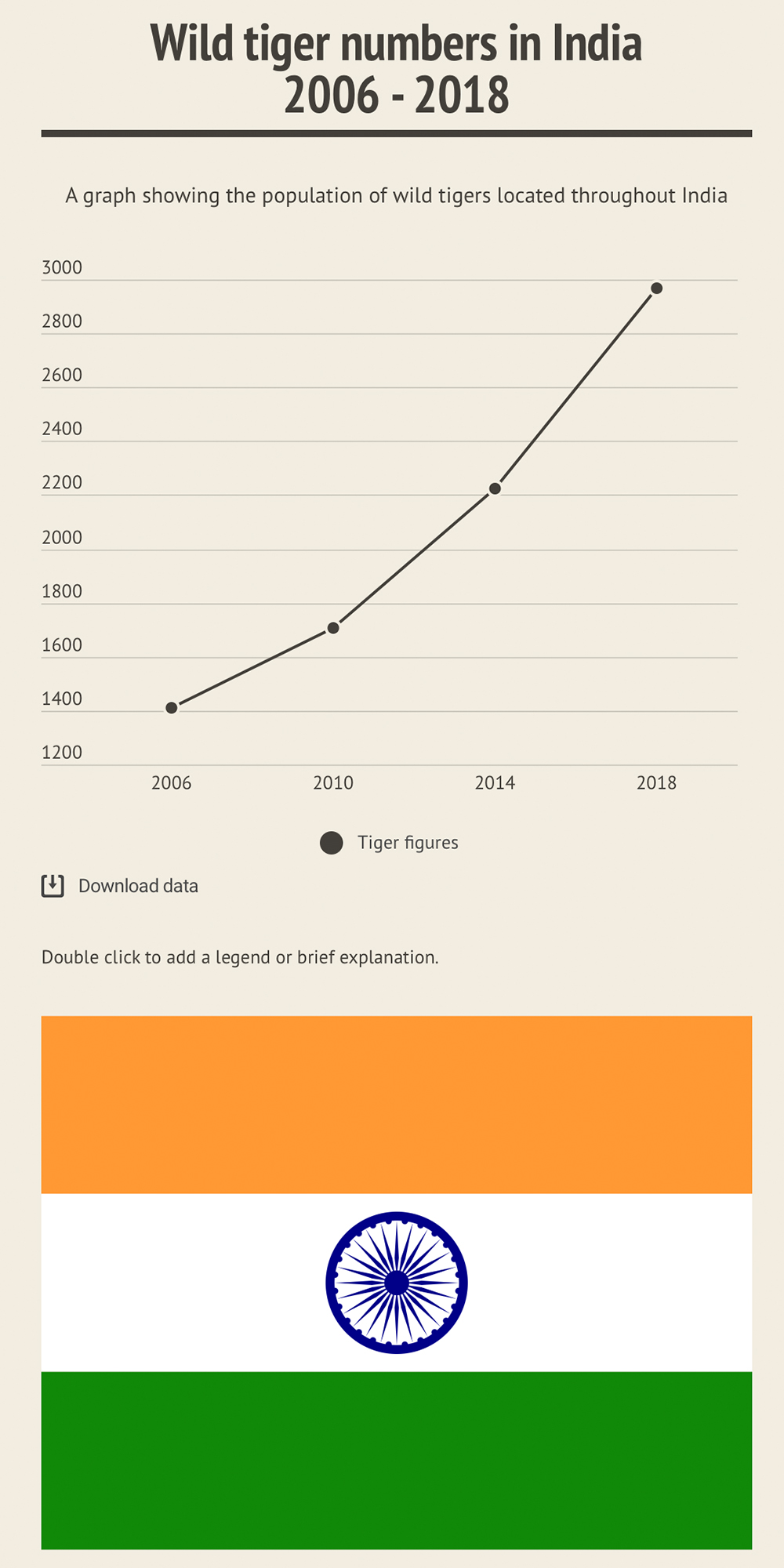

On the east of Maharashtra, deep within the greenest of Indian rainforests, lies six tiger reserves that unbeknownst to many locals, have just achieved something remarkable. Together, the likes of rangers and conservationists work relentlessly, day and night, and their actions have increased the tiger population in this state by nearly 65% since 2014. Now, locals sleep with 312 of their country’s national animal roaming freely throughout these reserves, compared to just 190 four years ago. In India as a whole, it has emerged during their traditional four-year census that tiger numbers have now doubled from 1,411 in 2006, to just fewer than 3,000 today.

With its unique stripes and balletic stroll visible from afar, the tiger is a showcase of power and majesty. Those helping to save it have benefited the entire world by giving it the potential to continue as the planet's most spectacular big cat, despite it being nearly persecuted into submission. With India's forests home to more than 75% of tigers in the wild across the globe, this cat has shown that it can survive successfully in the most diverse of climates. Across the country, tigers embrace the driest surroundings of dusty savannahs, as well as unbelievably cold grassland temperatures during winter nights. These conditions demonstrate the strength of a cat so resilient that it will always find a way to survive given the opportunity, even when the odds are stacked against it. But how does saving this animal benefit the rest of us?

Revered by people in all four corners of the earth, the tiger’s feline charm and colourfully-striped pelt make it a photographer’s dream. They are a beautiful sight that deserve to live peacefully, not relentlessly hunted down into extinction. Yet tigers are more important to us than simply being big cat eye-candy.

The apex predator plays an integral role in the way it shapes the earth’s ecosystem. Their rapid exodus from nature has resulted in huge amounts of water-producing and carbon-generating forests they resided in disappearing with them. When deforestation causes tigers to depart the planet, it also ensures the jungles in which they live in depart too, as new settlements replace the now-crushed greenery of nature before them. This means that carbon is continuing to be released into the atmosphere and cause further damage to a planet this is already struggling to maintain itself. If the tiger were to be wiped out, you eliminate more of these forests and jungles that we as humans need for oxygen to survive.

The tiger’s position at the top of the food chain also allows them to crucially control the habitats of all the other species with whom they co-exist. When a tiger hunts for prey, it forces all parts of the chain to constantly move to stay alive, meaning no-one ever stays in the same place. This allows vegetative producers like grass and plants to continually regenerate, and this is extremely significant. If all animals stayed in one location, ecosystems would be destroyed because biodiversity could not be achieved without them. This interdependence makes tigers’ existence pivotal, because they allow the environment and all those living in it to flourish. It shows that when tigers thrive, so does the rest of the world.

This can be best seen not only in India, but also on the island of Sumatra, home to the Sumatran tiger sub-species. Along with the Sumatran elephant, rhino and orangutan, these animals together form the Leuser ecosystem, in what is one of the most ancient rainforests on the planet. This habitat is central to all forms of life, including the four million people living here, as its forests supply water and allow surfaces like soil to grow and create crops. As the apex predator, tigers are the starting point for creating healthy conditions to their surroundings, and Sumatra displays the instrumental role they play in maintaining balance in their landscape.

With tiger populations rising by a third throughout India in just four years, their vulnerability status is reducing gradually for the time being. Despite a more complete revival still possible, this animal continues to be plagued by obstacles both new and old. It must notably continue to compete for its existence in a country whose own population is changing in quite the opposite way. Now on the verge of a staggering 1.4 billion inhabitants, over 80% more than at the start of the previous century, the number of wild tigers in India has diminished by nine in ten tigers during the same period.

With around 12,000 also kept in captivity and as pets primarily across the USA, a mere 3,900 of these cats are left living naturally across the planet. Most importantly, a little over a thousand of these are breeding, female tigers key to keeping the animal with us going forward. With each male cat also needing a territory of 100 sq. km, the equivalent of more than 18,000 football pitches, leading tiger expert Dr. Ullas Karanth says India’s recently increased figures are still not even close to the animal’s native and global potential.

"India possesses 25% of all potential wild tiger habitat globally, which is about 300,000 square kilometers,” the former director of the Wildlife Conservation Society for India says. “India should have a vision of 15,000 tigers given what is possible, and the world should have a vision of 50,000 wild tigers spread across 1.2 million square kilometers in which they can still recover and thrive. We all need to infuse a lot more science, passion and pragmatism into tiger conservation to make that vision a reality."

Living in a country so crowded has meant isolation has become more and more difficult for the tiger. As it searches for the vast and expansive area it requires to survive, many reserves in India are built on the periphery of cities. The continuous erection of new homes, roads and infrastructure has resulted in the boundary between tigers and people becoming ever more broken, causing human-animal conflict that has nearly destroyed the species. Ultimately, this predator is becoming increasingly limited to where it can live and what it can hunt.

Their ever-decreasing territory ensures they have no choice but to voyage towards human settlements nearby, where preying upon farming livestock has inevitably caused anxiety for local villagers. In July this year, seven tiger deaths were recorded in Nagpur in the space of just 12 days due to poisoning, simply because the border of their habitat had been diminished to make way for crops. Deaths are now so common that the government has focused far more intently on improving the position of the predator this decade. Their main goal has placed a huge emphasis on moving people local to tiger strongholds away from these areas, and placing them in new villages further away.

In the hills of central India, a non-governmental organisation called the Satpuda Fountain has been doing just this. Home to over 300 tigers, president Kishore Rithe says relocating villages is something that will prove decisive in driving the species’ numbers up further throughout such an overpopulated country. "Village relocation has been a game-changing step to the tiger population increasing,” explains the founder of the largest continuous tiger habitat in the world.

“It was decided to relocate and resettle 273 villages in 2005 from core areas of tiger reserves, but only a few states like Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka showed interest in doing this. The government of Maharashtra has relocated around 32 villages in 2015 from tiger bearing protected areas, and provided 3000 hectares of core area to allow safe breeding of tigers. Very few states in India have implemented village relocation programme for tigers so successfully."

Such schemes have long been aspired for by tiger conservationists. Being able to live and breed undisturbed will arguably continue to prove the biggest influence in protecting a cat that can already reproduce in some of the harshest conditions worldwide. Sariska National Park has seen its tiger population rocket from zero back in 2005, to 14 today as a result of 29 nearby villages being relocated. Meanwhile, 12 villages were relocated in the heart of the Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh in 2009 to allow successful tiger breeding. The number of tigers here now stands at an even higher 47 adults, again up from zero when the scheme was implemented. It is no surprise to see that tigers are now roaring in areas that have implemented village relocation with the extra space the animal now has access to.

Ironically, the stature and eye-catching looks of this beautiful cat has also contributed to its rapid downfall. Although India has banned tiger hunting since 1971, the animal’s illustrious prestige has meant that it is still classed by many hunters today as the pinnacle of trophies. Only individual pioneers such as Indira Gandhi in the 1970s fought vigorously to help tigers survive in the country, even when numbers plummeted as low as just 1,800 at the start of her reign in 1971.

The former Prime Minister implemented strict hunting laws and also launched Project Tiger in 1973, a conservation programme aimed at trying to stop tigers being massacred throughout the country. The project helped numbers rise to around 4,000 by 1984 before they dropped to roughly 3,000 by the mid 1990s. This downward spiral continued until barely 1,500 tigers remained at the start of this millennium; the species always fighting a seemingly-infinite, losing struggle as its body parts became a more illustrious prize.

In India as a whole, it has emerged during their traditional four-year census that tiger numbers have now doubled from 1,411 in 2006, to just fewer than 3,000 today.

While illegal poaching is becoming less common throughout India, the trafficking of tiger parts still takes place in the country today. Recent incidents have been widely documented across the country’s media, and are causing India’s hierarchy to take stricter action. Inflicting higher prison sentences upon those found guilty is now common practice, notably in 2018 when five poachers were each sentenced to seven years in prison for hunting crimes in the district of Betul.

As governments at both regional and state level fight to control the issue, a host of anti-poaching ranger patrols have been set up in reserves and national parks across the country. In 2012, Maharashtra went as far as to no longer considered it a crime for forest guards to shoot hunters, as they legalised the killing of poachers across the region. The state of Uttarakhand in August 2019 also created a Special Tiger Protection Force, which consisted of 85 forest guards spread across the world-famous Jim Corbett National Park. Likewise, 24-hour security was put in place at 95 camps across Bandhavgarh’s National Park, a place which is today home to between 60-70 tigers.

These efforts have proven essential in giving this cat a fighting chance at their future, especially as sub-species like the Sumatran and Malayan tiger find themselves on the brink of annihilation in their native homes. Used for their pelts across the black market, and particularly as a method for medicine for over 4,000 years, China has potentially sealed the fate of these tigers by no longer making it illegal to use the animal’s bones for medical purposes.

With both the Sumatran and South China sub-species also on the verge of extinction, each with wild populations of less than 700, hunting has proven monumental in this animal’s precarious future. It has led to the devastating announcement in October 2019 that the Indo-Chinese sub-species are now declared extinct in the country of Laos. This highlights that whilst India is preserving the species and is seeing the number of tigers rise through its anti-poaching measures, the same cannot be said for many of its neighbouring Asian countries.

A further step that has been introduced in allowing the cat to recover in India is through the use of tourism. With extinction still a major possibility, many have flocked to see an animal that could cease to exist in decades to come. With the likes of Bandhavgarh’s National Park generating an estimated 100,000 visitors each year, authorities have been able to convince many neighbourhoods that the tiger is a great economic asset; which is far more beneficial to them alive than dead. This is something emphasised by Sharad Kumar Vats, founder of Tiger Safari India and an expert who has worked in tourism conservation for nearly 20 years in the country.

“I have always maintained that regulated tourism is an important conservation tool,” he explains. “After 2006, when the numbers went down and two national parks lost all their tigers, there was a big concern around the world. Everyone got their act together and focused more on conservation. Park rangers and their team have played a big role in this, and also the census methods have now improved.

“There is increased awareness worldwide, especially within India after social media arrived. The advent of wildlife tourism has played a major role in conservation. The increased number of Indian tourists in the last few years posting images on social media means everything gets noticed and reported. Lots of new lodges have come up around the parks, thus generating employment and starting an economy in the area, and this is good for wildlife as locals recognise the importance of tourism as it brings them money - so they help conserving it.”

For locals, being able to increase their profit is one thing, but tourism has also allowed a deeper connection to form between themselves and tigers. Realising its steep downfall, villagers have been able to use their location’s influence to alter the tiger’s portrayal from a deadly monster to an endangered cat. Yet not all conservationists have seen tourism in the same light. Some believe that the animal suffers higher amounts of stress with daily vehicles circulating their landscapes.

This led to India’s Supreme Court making it clear in 2012 that regional governments needed to regulate tourism more effectively, although notably they didn’t prevent it taking place altogether. With people able to gain closer access, it has even been suggested that tourism has given poachers a free pass to hunt tigers more easily, although this has yet to be proven. What has been made clear is that the use of tourism has formed an alliance with tiger conservation. However, with many reserves now said to be on the verge of being overpopulated with the species, whether tourism continues to do so will only be made clearer during the next census in 2022.

But are this year’s figures just a brief period of false hope? It cannot be disputed that what has been achieved this decade by India has been revolutionary for the species’ future. However, many believe there’s still a long road ahead with further problems on the horizon. Environmental scientist Matthew Hayward says that even if tiger numbers continue to grow, this will still lead to further obstacles for them.

“The resources the Indian government has invested in conserving the species - via research, park creation, and anti-poaching management illustrates that if you invest in conservation, you can make real achievements,” the former WWF conservationist insists. “Rangers have also helped via these anti-poaching patrols, but also via assisting researchers. It's obviously a good thing that tiger numbers have increased in both the short and the long-term, although this will create problems ultimately with overpopulation and not enough places to repopulate.”

Tiger conservationist and co-founder of charity Tigers4Ever, Corinne Taylor-Smith, also echoes that overpopulation could be an issue going forward for the animal. She believes that a note of caution should be given surrounding the accuracy of increasing tiger numbers, especially since the country’s first conducted census back in 2006. She also hints that not only could wild tiger numbers have been calculated wrongly in the past, but also that numbers could actually decrease by the time of the country’s next census.

“There are a number of reasons for the steady increase in wild tiger numbers in India, not least the way that modern tiger census data is captured when compared to the past,” she says. “Before 2010, the tiger census was done by the old-fashioned pugmark identification method, which involved plaster cast impressions being taken of tiger pugmarks along transects - the segments in which tiger territories were divided for the count. This wasn’t very scientific - there was a margin of error because the same tigers could be double counted if their territories crossed two transects.

“In its favour, it only recorded the number of adult tigers - those over 3 years old. Only counting adult tigers is important because tigers do not usually establish their own territory until they are around 3 – 3.5 years old. By 2010, the census included cubs over the age of 18 months and adults. The final count was 1,706 up from 1,411 in 2006, but we were concerned that there was no indication of how many sub-adults were included in this figure.”

"It's obviously a good thing that tiger numbers have increased in both the short and the long-term, although this will create problems ultimately with overpopulation and not enough places to repopulate"

Although Taylor-Smith agrees that last year’s figures were the most representative of all so far, she raises doubts over whether numbers as recent as 2014 could also have been inaccurate. During this time total numbers grew 30% from 2010, although the census counted cubs aged one year and over plus adults, compared to counting tigers over the age of three in 2006 and tigers older than 18 months in 2010. She adds that expanding the age range of the population, as well as not differentiating between the numbers of sub-adults (cubs), means it is hard to know whether numbers have been concrete since populations were first calculated.

“By 2018, the census was the most scientific to-date,” she adds. “The transects covered a much wider area and for the first time counted tigers outside protected habitats. The data is probably the most accurate to-date because the methods used included beat recognition (visual references/tiger sightings/pug analysis), camera trapping over a much wider area, DNA analysis and stripe pattern recognition. On the downside, cubs aged 1 year plus were again counted and not distinguished from adults in the final stated results.”

Despite last year’s count being the most meticulous so far, another rise in the tiger’s population isn’t necessarily guaranteed. Taylor-Smith emphasises: “Many protected tiger territories have reached or are close to carrying their capacity, so there is nowhere for increased numbers of wild tigers to go,” she insists. “Without a commitment to increasing their habitat, tiger-tiger conflict and human-tiger conflict will increase, having an adverse effect on both current tiger numbers and those at the next census. However, with commitment delivered, and the continued protection via anti-poaching measures, wild tiger numbers in India could potentially increase by another third to around 3,800 by 2022. If, however, nothing is done to address the lack of safe suitable tiger habitat and schemes like road widening go ahead, it is likely they will go down.”

With India slowly reaping the rewards for its conservation efforts over the past decade, the tiger’s future appears less precarious than it did at the start of this century. A raft of new laws by the country’s government as well as efforts by local and global conservationists have at least improved their still knife-edge position. However, optimism should remain grounded. The fate of the species is still unknown in the short-term, and extinction is still possible in decades to come. But even in a country so crowded, both tigers and humans can live in harmony together, as we have done for over 12,000 years. Even though it is our behaviour which continues to impede their survival, the tiger's fate remains in our hands, and only our hands can allow this animal to keep going from strength-to-strength.