Alice Beckett

In a world where we can see herds of elephants traipsing through their wild African habitats on a box from the comfort of our living rooms, Alice Beckett asks, do exotic animals still need to remain in British captivity in this day and age?

Love them or loathe them, zoos are presented to the public in near enough every big city in the country. They continue to be controversial amongst conservationists, biologists and ecologists, to name a few. It’s no secret that zoos have evolved massively over the years, from animals being confined to traditional barred cages and tiled flooring, to up to 500 acres of grass, sand and rivers.

Let’s take it back a century or two, and look at the first ever zoo to open in the UK, the ever-popular London Zoo. In 1847, the institution, originally used as a collection for scientific study, opened to the eager public. To a Victorian nation, this was like nothing ever seen before, most having never even crossed the border. Wild bears, onyx’s, and orangutans roaming around their enclosures brought new, exciting days out for families, and opportunities for experts to observe animals from foreign countries.

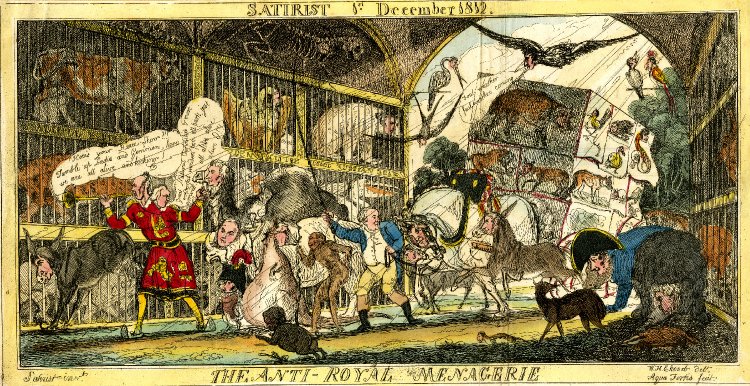

Travelling zoos were the height of the eighteenth century, where both domestic and exotic animals were paraded up and down the country for the entertainment of the public. In the 1860s, animals were even held captive in Harrods, appealing to wealthy customers who purchased a variety of exotic animals from tiger cubs to alligators.

For a lot of us, some of our fondest memories involve summer days out to the zoo, seeing animals we wouldn’t otherwise see if they didn’t exist. Most of us don’t have the opportunities to venture through the African desert or wade through the Indonesian rainforest. Visiting a park where there are collections of these animals was our only way of seeing the animals in real life.

Of course, zoos have changed drastically since the 19th century, enclosures are a lot more open and similar to natural habitats, animals are free to roam about a wider space of land. According to a study by Plymouth University, “empty, boring, barren enclosures” can cause depression in some animals. Zoos are seemingly doing all they can to ensure this isn’t the case, and animals live a better, more enriched lifestyle.

Chessington World of Adventures introduced Europe’s first overhead tiger enclosure, The Land of the Tiger, where the wild cats are free to wander around a large bridge overlooking the animal park.

In an interview with The Sun, the animal park said: “We believe Land of the Tiger and its innovative, specially designed enclosure formed of three habitats, featuring European first overhead trails allowing the tigers’ freedom to roam, sets a new standard for animal care and welfare – which is always our priority.”

As well as allowing for tremendous sights for visitors, the enclosure allows the tigers a different type of home, contrasting with the traditional rectangular pen, making them less likely to suffer with boredom.

After 18 months of building, the family of endangered tigers were moved into their new and improved home just before the summer in 2018.

But living in a different world, where we can easily switch on the TV and watch a David Attenborough documentary, seeing animals in their natural habitats exhibiting natural behaviour, surely, we don’t need to hold animals' captive anymore to understand them. Or do we?

In European zoos, 70-75% of animals are not globally threatened in the world.

—Damian Aspinall, owner of the Aspinall Foundation

Stereotypies are one of the main arguments as to why animals shouldn’t be kept in captivity. Most people who have visited a zoo will know that it’s not unusual to see animals in enclosures behaving abnormally. Plucking out hair and fur, pacing up and down, and general anti-social behaviour is commonly seen in zoos.

Biologist and University of East Anglia lecturer, Professor Ben Garrod, says:

“All modern zoos should work as hard as possible to ensure there are ideally no psychological stresses. It’s not just enclosure size, you could have a smaller enclosure that is full of enrichment or a massive enclosure that is terrible, so it’s about finding the right enclosure for the right species.

“What will work for one tiger, for example, won’t work for another, so it’s about zoos really knowing their particular animals.”

Of course, there are good zoos and bad zoos. In most modern zoos, zookeepers have a duty of care when it comes to animal welfare.

He adds,

“A lot of work, both academically and within the zoo community has gone into trying to understand stereotypic behaviour and it represents very differently in different groups.

“We’re at a place now, where I’m aware as a broadcaster, we can show you things through TV or on YouTube that we couldn’t have done 20 years ago. You can see a polar bear with its cub in the Arctic, you don’t need to see them in captivity.

“However, the argument is, by having this closer interaction, by being able to see an animal just feet away from the other side of the glass, or gorillas across an island aligns with interaction that can inspire people, and hopefully inspire them to care more and become ambassadors themselves.”

As pointed out, the quality of a zoo is certainly subjective. Modern zoos have a duty of care when it comes to the welfare of the wild animals, forcing them to replicate their natural habitats.

Dr Garrod also adds that zoos are the “perfect opportunity” to talk about and engage people in the climate change crisis, as well as biodiversity loss.

“I think there could be a real shift in the way zoos operate and I think that the more that zoos embrace technology, we’ll see them improve vastly.

“A lot of zoos in the UK love dinosaur exhibits and displays – of course, they’re not animals that are even alive. I think utilising virtual reality would be a really strong way of both communicating conservation and not needing some of the species we currently have in captivity.”

South Lakes Safari Zoo is one of the proclaimed “bad zoos”, after 500 of its animals died horrific deaths in a mere four years. The deaths included two snow leopards found partially eaten in their enclosures, and tortoises dying from hyperthermia.

Since opening in 1994, the zoo has been subject to the utmost of scandal and controversies – from a zookeeper being mauled to death by a tiger in 2013, to constant abnormal animal welfare issues.

A former zookeeper at the park said the food for the animals was “inadequate”, and the baboons would be fed leftovers from supermarkets. He told The Guardian of his resignation after two spider monkeys attacked a third, they “ripped his face to bits. He was stitched up a bit and put in a separate area, but they just left him there for days. I repeatedly asked why they weren’t putting him somewhere safe. He died of septicemia.”

And it’s not just UK zoos who have faced accusations of improper care when it comes to their animals.

Concern for caged animals became of global mainstream interest even more in 2016, when Harambe the silverback gorilla was shot dead after a young boy climbed into his enclosure, in Cincinnati Zoo in the United States. The 3-year-old boy crawled over a 3-foot wall, and made his way into the colossal creature’s enclosure, before being dragged by his arm through the water by Harambe. The 17-year-old gorilla was then shot by a zookeeper, fearing for the child’s life.

Harambe’s enclosure, made up of cliffs separated by a moat, was heavily criticized for the incident. Designed to replicate the giant primate’s natural habitat, the area was easy for the small child to climb into.

Though many people blamed the parents of the boy, the zoo was also condemned for immediately shooting the gorilla. This sparked a global debate among primatologists and biologists on whether the animals, mainly native to Africa, should be kept in captivity.

The question still remains: can animals enjoy more natural enclosures without being hazardous to the public?

Birds are unsurprisingly a species most affected by captivity. Flying about freely in the wild, to being confined to a single space surely has consequences for the wild animals. They often display stereotypies in their enclosures, feather plucking being the most noticeable. Nothing will ever compare to the animals being able to fly candidly in the natural world.

A University of Sheffield study showed a number of birds who suffered extremely high rates of embryo death, mainly due to inbreeding. Nicola Hemmings, who led the research believes this may be due to “the stress of a captive environment.”

She told the university,

“Our findings suggest that breeding birds in captivity may impact on their fertility. The captive birds we studied had high levels of infertility and far fewer sperm managed to reach the eggs than would be expected of birds their size.”

In 2018, Freedom for Animals, a charity campaigning against animals being used for entertainment, launched an investigation into the treatment of birds of prey in captivity. Their shocking findings included birds being tied down for most of the day and only being flown for an average of 11 minutes daily.

Other discoveries made by the organisation was the public having close interaction with the birds, allegedly resulting in elevated stress levels.

Nicola O’Brien, Campaigns Director for Freedom for Animals said:

“We found many zoos with enclosures that were really small, and there was not a lot in there to enrich the animals. Birds were being tied down for hours on end by their legs. We found animals without clean, fresh drinking water.

“When we looked into the training processes around how they do bird displays, we discovered that amongst the training methods they use is holding food, so the birds would go for days without food.”

Of course, there are many counter arguments, the main being that zoos are important for conservation and to gain a deeper understanding of species. In order to protect the animals in the wild, some need to remain captive in order for specialists to observe behaviour.

Monitoring an animal that is kept in captivity, for example, is much easier than an animal that is free to drift around a forest or desert. Zoo animals act as a representative of their counterparts in the wild, and so could play a part in the protection of the species as a whole.

The British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums (BIAZA) represent over 100 zoos and aquariums across the UK and Ireland, including London Zoo and strongly believe that an institution such as a zoo is important for wild animals.

“We would like to point out that zoos and aquariums have evolved enormously over the last few decades, from menageries based purely on entertainment and recreation – often with questionable welfare standards – to scientific hubs of animal care expertise, research and conservation.

“Our staff are highly qualified, experienced and passionate about the animals in their care and work tirelessly to ensure they have the best possible quality of life.”

Reintroduction is also set to become a success, after ecologist Derek Gow announced the first wildcat breeding ground in the UK, despite their extinction in the nineteenth century.

The expert on mammal reintroductions aims to breed the cats, which he got from a zoo, and release them back into the wild in three years’ time. Experts expect the cats’ release into the wild from captivity will result in a rapid decline in grey squirrels, who aren’t native to Britain.

Recently, reintroduction has been a method adopted by wildlife parks in the UK. The Aspinall Foundation, owners of Port Lymphe, Howletts Wildlife Park and Wingham Wildlife Park, released a range of endangered animals back into their natural habitat. The animals reintroduced include 8 black rhino, 11 European bison and over 70 western gorillas. The charity’s priority is conservation, “through captive breeding, education and reintroduction.”

There seems to be a heavy emphasis of the fact that the animals aren’t in long-term captivity, and will be reintroduced into the wild eventually.

Damian Aspinall, owner of the Aspinall Foundation and the three Kent animal parks, said:

“There is no need for any wild animal to be in captivity in zoos.

“In European zoos, 70-75% of animals are not globally threatened in the world.”

“Zooaucracies and zoo-rocrats have a stamp collector’s mentality and an appetite and a preference to please the public for ironic and non-threatened species”, he adds, “leading to their needless captivity and consumption for entertainment.”

These days, zoos are not all considered equal. Most of us would agree that the zoos of the Aspinall Foundation, which provide acres of land, and different habitats for its wild animals, and the grim setting South Lakes Safari Park once was are on different ends of the spectrum. But categories are not always that clear cut.

Animals in captivity is the common denominator in the institutions, taken from their wild habitats and placed into confined pens and enclosures. However, zoos won’t be eradicated in the foreseeable future – so, should we just go along with them regardless of whether we agree or disagree?

Zoos make a lot of money from visitors, particularly in the summer holidays where they peak massively. According to a Born Free report, the Consortium of Charitable Zoos (CCZ) spends an estimated 4-6.7% of gross income on conservation in the wild.

Entry fees averaging at around £10.30 per ticket, that would mean only 46-70p would go towards the conservation of animals in the wild.

In recent years, London Zoo announced “Zoo Night”, which is essentially an adult-only event where alcohol is provided and street food, amidst the animals. However, when the rowdy public began throwing alcohol over the creatures and visitors allegedly getting “touchy feely” with the baby penguins, the zoo faced more controversy than ever before.

The incidents also included a man stripping off and attempting to get into the penguin enclosure, and a drunken woman trying to enter the lions pen. A group allegedly cracked the glass on a snake tank, forcing the snaked to be moved.

But while many would blame the foolishness on the perpetrators', the real offenders would be the zoo managers, who put profits before the welfare of animals. Tickets averaging at £35 per ticket, a £10 price increase from a day pass – some would argue that zoos don’t contribute enough to conservation, putting the ‘con’ in ‘conservation’.

Nothing will ever compare to their own habitat; nothing compares to them being free and that’s all animals want – to be left alone.

—Connor Anderson, co-founder of Evolve Activism

Animal rights liberalist, Connor Anderson is no exception. The co-founder of Evolve Activism suggests that zoos only exist to make profit and are a continuous money-maker, as part of an aristocratic tradition. He says,

“The fact is, zoos are entirely profit-driven. The only reason why they exist is to parade animals for humans to have a look at.”

Animal rights liberalist Connor Anderson suggests that we focus on the bigger picture of combatting climate change, rather than keeping the animals locked away in enclosures.

He adds,

“Zoos will often say the only reason they keep animals there in the first place is to protect the species. There are much more effective ways of doing this. Many reasons why these animals are going extinct in the first place is due to human activity, whether it be down to poaching or through man made climate change, which has a massive impact on their ecosystems.

“Rather than just keeping them locked up, to keep them alive, wouldn’t it be better to tackle the root cause of the problem as to why they’re going extinct in the first place?”

Though the argument surrounding zoos is certainly a sensitive one, many would argue that there are elements of hypocrisy in the debate. With just 7% of the UK population being vegan as of 2018, do we have bigger fish to fry when it comes to animal welfare?

Animals held captive in zoos are usually the more exotic, better looking than a muddy pig or mangy looking chicken. Are the lives of elephants more valuable than the lives of chickens?

The co-founder of Evolve Activism adds,

“The animals are bored and traumatised. Nothing will ever compare to their own habitat; nothing compares to them being free and that’s all animals want – to be left alone.”

In 2014, it was reported that a lioness and her cubs in Longleat Safari Park had been destroyed due to “serious genetic defects caused by inbreeding”, after displaying abnormally aggressive behaviour.

The Amur lion, named Louisa, was aggressive to the other lions and therefore the zoo made the decision to put her down.

It was argued that the Wiltshire zoo’s negligence allowed this to happen, as there would’ve been ways of preventing the overpopulation happening, such as a contraceptive pill.

Poor keeping of the animals seemed to be a factor in how the incident happened, and again, made for the public questioning whether these animals should be kept in enclosures, or used for breeding programmes.

Similarly, a case of animal abuse was reported in 2012, after zookeepers were seen “beating” African elephants in Twycross zoo, in Leicestershire. Two sadistic men can be seen on the recording “beating the elephants with canes”.

The men were set free and not charged, however were sacked from their jobs instantly.

Whether you agree or disagree with zoos, ultimately, they still will most likely continue to exist and thrive in the future.

A way around this would definitely be working alongside zoos to make them as best as they can be for the animals. The idea of zoos isn’t as black and white as people think. If zoos allow for more people caring about the natural world, then does that make them worth it?

In the long run, animals being kept in captivity isn’t never going to be ideal and will never be a natural way for them to live. But zoos have existed for centuries, and it doesn’t look like they will close their gates any time soon.

Featured image by Gerald England