The world of dance really is a world of its own.

The intense, demanding, and exhausting nature of it places inevitable pressure on dancers involved in more ways than one.

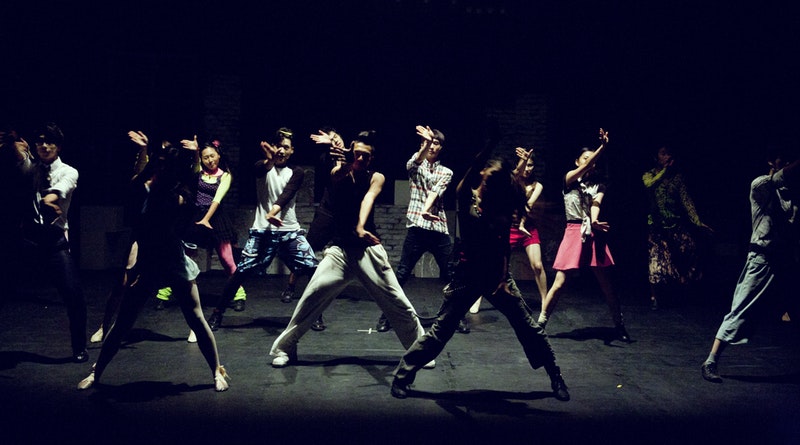

When watching a performance, a show, or dancers competing against one another, all you see is the smiles and the exuberant facial expressions telling a story, and the high kicks. What you don't see is the endless hours of rehearsals, the blood sweat and tears which come with training or the constant lack of energy and fatigue which the dancer hides from the audience.

Being a dancer is something considered by many as a glamorous status, a talent and something to be proud of. Yes, it is something to be proud of however it is also an industry full of impossible standards.

With this issue mainly being associated with ballerinas, however from personal experience this being something associated with a wider range of dance styles: as a dancer you can feel so many mixed emotions.

You don't feel skinny enough, your waist isn't tiny enough, your legs are not quite the right shape, you hair doesn't sit in that perfect bun and you aren't as flexible as the girl next to you in class.

These are all individual battles in their own right that I can guarantee each dancer reading this has previously experienced.

As a dancer, people think there is an ideal weight, height and shape.

However this could not be more wrong.

In the real world, especially within our society, there is no "ideal body" or vision of perfection. As the years have gone on body appreciation and body confidence has been hugely encouraged and promoted by everybody, celebrities and instagram influencers are all for "be happy in yourself"... something that the world of dance needs to adapt to.

One thing that young girls and boys do not understand is that the peak time of your body changing is your teenage years and going through puberty, often a time when children and young adults thrive in their dancing years. To have a young adult idealising a specific body or being ashamed of their so called "imperfections" is something which often shows signs of Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD).

Body Dysmorphic Disorder can be defined as a psychological disorder where somebody becomes obsessed with perceived defects or flaws in their appearance. Often, the flaw is not as prominent as the suffer perceives it to be, for example they see a part of their body as double the size than it actually is.

It can be characterised simply as excessive body self-confidence, however this isn't just feeling self-conscious as this can contribute towards a much bigger issue.

Many individuals who feel this embarrassed by their so called 'flaws' will not believe anybody who tells them otherwise and will avoid wearing certain clothes or even leaving the house in extreme cases as an attempt to camouflage their problem.

Behaviours of an individual suffering with BDD:

-constantly checking their appearance in the mirror

- picking skin or constantly touching their hair to make it 'just right'

- comparing themselves against others

- discussing their appearance/ body shape with others

- seeking compliments and praise related to how they look

- camouflaging their appearance or outfit choice

Despite this being something all dancers hear of, it really does happen, often to people closer to you than you think.

Kerry and Anna (whose names have been changed to protect their identity) are a part of the dance troupes at a university in Canterbury, both who have previous dance experience from a young age.

Kerry said: "I started dance at age 12 and when I was 13 I developed anorexia. I don't believe this was a direct result of joining a dance school but I do believe it had some influence. Most of the people there were thin and I had a very muscular figure, which at the time I considered to be fat or obese. Even after 'recovering' from my eating disorder, I still had a lot of issues mentally with my body to the point where I wouldn't go out in public without a skirt, dress, long cardigan or long coat for 3 years.

"However, when I joined dance at University I noticed that a lot of people had mature womanly bodies, and not everybody was super thin. This helped my confidence because I always compared myself to people younger than me who had child like bodies (such as the girls on dance moms) and not to those who were actually my age and had mature figures too.

"I can see how far I've come as now even if my brain says negative things about the way I look or feel in a costume, I can ignore them."

Anna said: "Being a competitive dancer since I was 5, I grew up at my dance school and had to deal with my changing body. I can remember at the age of 11, the year of our dance show and the process of trying on costume and the initial feeling of being different.

"My close friends at my dance school were able to wear the smallest size costumes whereas I had to go up a couple of sizes. I was nowhere near fat, but at a young age I could see that my thighs and arms were bigger and my belly had a bit more fat on it. From then on I became more and more aware of this, watching back at DVDs of my dance show and finding myself unable to not stop looking and analysing my body, crying to my mum about how good everybody else looked in their costumes and dreading the day my dance teacher would crack down on uniform and make us wear only a leotard and tights to class, as I'd be so insecure about my body.

"This negative perception carried on well into my teenage years, I was always very selective about what I would eat, but would always feel so defeated when I saw some of my friends eat the most unhealthy food yet it would never affect them.

"Since joining university I've found that my body dysmorphia has not gone away. Despite being able to now wear a leotard and tights and not have the agonising feeling of everyone looking at my 'lumps and bumps', it is still an issue which concerns me. I don't have abs and my thighs still move when I move. Body dysmorphia has still affected me in my confidence and dance in everyday life."

According to the International OCD Foundation which is dedicated to providing resources for OCD and related disorders such as BDD, the disorder affects 1.7% to 2.9% of the general population.

This is equivalent to 1 in 50 people.

Despite this being a poor statistic in itself, this could even be a higher statistic as many suffers are too afraid to admit their symptoms or do not want to categorise how they are feeling as a 'disorder'.

This figure of 1 in 50 is one too many people feeling like this and with dance being a huge contributing factor, individual dancers need to be encouraged to find self confidence prior to joining such an intensely demanding industry.

Dance in nature is competitive, however it should be about self-esteem, growing as an individual and improving your skills no matter your shape or size.

From personal experience and hearing from other individuals who dance in dance troupes at University, University dance appears to be the most inclusive and motivating form of dance, despite it also being competitive.

This is something that universities across the country should be proud of, and professional dance schools should therefore inevitably be taking a leaf out of the University dance world's book.