In the time that it will take you to read these two sentences, yet another person has been reported missing in the UK. Chloe Selvester talks to those who dedicate their lives and careers to a search that might never end.

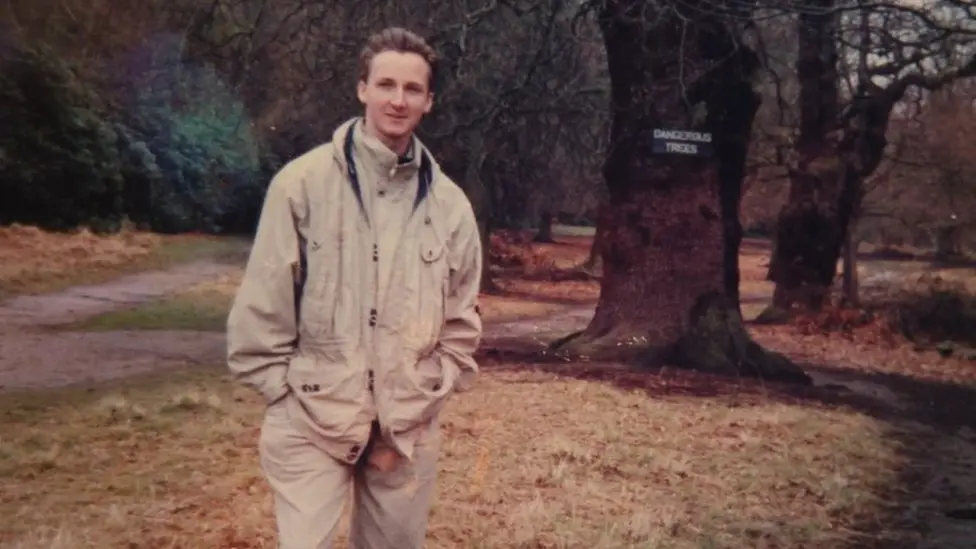

Trevor O’Donnell was seen by his family as a bright, quiet but eccentric man who was excelling in his physics degree at University College London.

One day the 23-year-old abruptly left his studies to pursue a career as a lab technician in Canterbury.

A few days into his new job, Trevor wrote to his manager to say he was going away for a few days.

This was the last anybody heard from him.

It has now been over 30 years. Trevor is just one of 170,000 people who go missing in the United Kingdom every year.

Marlena O’Donell never had the chance to meet her brother-in-law Trevor but has seen the heartbreak first hand as his family have never stopped searching.

“He left without any note, any passport and we haven’t heard from him since,” she said.

“It’s left a Trevor-shaped hole in our lives. His absence is his presence.

"The not knowing is more painful than knowing, if we didn’t want to know then we wouldn’t look. I think the fact that we keep looking, is an indication that any truth is better than not knowing."

Marlena admitted that the family have multiple theories about what happened to Trevor. Some are wild and crazy, some are more realistic. She would like to think that he is happy living somewhere else.

Poignantly, she recalled her wedding day in 1999. Five years after Trevor went missing, Marlena married his brother Kevin. The couple were desperately hoping that he would show up and that they would be reunited with him.

“Their dad died eight years ago, and he was so keen, like desperate, knowing he was dying and not having answers.

“It was his dying wish, and he died not knowing.

“When his dad died, we thought Trevor would come back then. We put the announcement in national newspapers, in The Times, because Trevor used to read The Times.”

Day-to-day life has been just as hard as the big life events for the family to experience.

“We could be playing board games together. Or I love art and travel. His brother Kevin said Trevor loved art too, so I could be going through art galleries with him.

"It’s kind of very much like he's missing out on all this, the life we could share with him, and we are missing out on that too,” Marlena said.

Sometimes families can even envy another family who've had news that their loved one is deceased, because they think at least you know what happened.

—Martha McBrier, helplines manager at Missing People.

The charity Missing People has helped 1,981 families like Trevor’s in the last year.

Missing People, founded in 1993, is the only UK charity that helps to support relatives who are left behind and offers a lifeline to people who choose to disappear.

Martha McBrier, helplines manager for over six years, explained that the charity does not physically search for missing people. Instead, they help to support the police with appeals.

“We can distribute posters of that missing person, and we can do other forms of publicity, like media, social media, we can even do things like huge billboards, to put out an appeal and promote the missing person,” she said.

The charity also offers bespoke support for families. Martha said that the effects can be extremely emotionally and mentally debilitating for loved ones who do not have answers.

“We have families that we've been supporting for over 20 years, where, sadly, their loved one is still missing, and there are absolutely no answers, no answers at all, and they experience this horrible feeling, which we call ambiguous loss.

“It’s very different from a bereavement, where you know what has happened, and over time, you can come to terms with that loss," she explained.

“We have a gentleman, and this is really heartbreaking, whose son went missing 10 years ago. He went missing in London, and he was last seen outside a tube station, and his dad sits outside that tube station every day, hoping he'll see him.

“Sometimes families can even envy another family who've had news that their loved one is deceased, because they think at least you know what happened.”

Martha added that some cases becoming high profile often takes her by surprise, but to the charity the search for every missing person is important.

“If you look at Sarah Everard and Nicola Bulley, these are two women who died, both in horrible circumstances. But people would say the media are picking those cases because these are white, blonde, beautiful women, and that a young black kid from East London, doesn't get any profile.

“How police even give these cases to the media, we don't know. But there is an inequality about what cases get high profile and which do not. They all deserve the big news flash on TV, and they all deserve the helicopters going round.”

Although there are 170,000 missing people reported every year, Martha affirmed that this number may be an underrepresentation of the real figure. Many people who are missing have not had their missing episode reported.

This could include people who do not have immediate family around them or are vulnerable and face issues like addiction and homelessness. “Sometimes even a body is found, and they've never been reported missing,” she said.

Martha admitted that her job can be challenging and it has affected her emotionally. “When you see their faces coming in on the referrals, you take a moment because they're not cases to be solved, they’re people to be found.”

We're not a chasing agency. Our role as the police service is not to find missing people, per se, because people are entitled to go missing.

—Alan Rhees-Cooper, missing persons specialist

The starting point for the search of a missing person often begins with a phone call to the police.

The National Crime Agency recorded that police in England and Wales received 312,901 missing person calls in the 2022/23 financial year.

This was an increase of 10% from the previous 2021/22 financial year, when 278,105 calls were made.

Alan Rhees-Cooper, specialist in missing persons investigations for 20 years, said the police will categorise the missing person into different levels of a high to low risk assessment with factors like age and mental health considered.

“We'd try and see if they've got access to a car or a vehicle, motorbike, and if they have got access to a vehicle, we can run automatic number play recognition that number through to see if that vehicle's been picked up on any of the cameras, anywhere travelling in any direction, we would identify places that they normally go.

“We could commence financial inquiries and see if they've drawn out any money, and where they've drawn out that money. We could request mobile phone data to see if they're using the mobile phone, and if they are then where that is mobile phones being used, which areas?

“If there's mental health issues or depression, we would contact the Mental Health Trust to see if they've treated the individual, to see what information they have.”

When a person has been missing for a long time, the police can also look at whether their mail has been received and conduct CCTV checks inside hotels.

“Ultimately, if we still struggling to find them, we would look at taking DNA samples and seize a toothbrush or a hairbrush. Or the financial inquiries which I mentioned and then loads of other agencies.

“We could start checking, whether they've applied for a passport, driving licence, have they asked for their driving licence address to be changed, that kind of stuff.”

Alan admitted that the police will not search for people who have chosen to go missing and start a new life. “We're not a chasing agency. Our role as the police service is not to find missing people, per se, because people are entitled to go missing. Our duties are around the crime, where there is concern that the person may have been the victim of a serious crime, then that's a police responsibility.”

The search operations for missing people have become televised events which gain publicity on an international scale. This was seen, most recently, over the summer through the well-documented and broadcasted searches for teenager Jay Slater and Dr Michael Mosley.

Lowland Search and Rescue was established in 1991 with just four original search teams. Since then, it has grown into a team of over 2000 volunteers and 36 teams across the United Kingdom.

Sean McCarry OBE, chairman, explained that the team will search for high risk missing persons once they have been alerted by the police. It is also not unusual for his teams to carry out searches for cold cases. “We cover from the high-water mark, to where a hill ends. And a hill officially ends, according to the survey at 2000 feet. So, we cover that hill to high water area,” he said.

“The hardest terrain to search is the heavy undergrowth and overgrowth. We have got bits of ground in every city, in every part of lowland area that would be equated to the Amazon jungle for want of a better word, except without the wild animals. You can't cut through the briars. It's very difficult to walk through them.

“We also have issues around fast flowing water and whenever there's heavy rains, you've got to watch the water courses, which are everywhere."

Sean explained that 70% of missing persons will be found within 500 metres of their last known location. He also stated that 50% of missing persons will be found within the first hour of searching. However, Sean was keen to express that he has conducted searches which have spanned across different countries.

“The weather does have an impact but that doesn't stop us. Nighttime does have an impact and that doesn't stop us, we just have to be aware of the added difficulties that compares to a nice, warm or even clear day with no rain and no cold.

“However, if it's too hot a day that's every bit as bad as in the wintertime. The heat can also have an impact, a negative impact on the quality of search and the welfare of the volunteers.”

“We’ve got a number of tools we can use, from drones to dogs to technology and other different types. And dogs are one of those, they’re a great asset to have. But even like human beings, they have their limitations.

“They can search actively, probably for 30 minutes, sometimes longer, but then they need a break, or their level of search drops dramatically.”

When a missing person’s disappearance has reached national news, members of the public have felt urged to try and search themselves. Many people descended on Nicola Bulley’s hometown in Lancashire with hopes to find her and some flew as far as the island of Tenerife to hunt for Jay Slater. However, Sean argued that this can do more damage than good.

“If we've got the public all over the area, and we don't know that they've been all through the area, then that gives us false leads, that destroys evidence and makes it more difficult. That also gives us a problem of having to look after the public and we also end up with lots of information that's wrong,” he said.

There are over 5,000 long-term missing people in the UK, who have not been found in over a year. One of the most well-known disappearance cases include Ben Needham, a British toddler aged just one-years-old, who went missing on the Greek island of Kos. As with every missing person appeal, it was his face that became most recognisable to the public.

It has been 33 years since he was last seen. Searchers are no longer looking for a toddler, they are looking for a 34-year-old man. The more time that has gone on, the more his appearance would have changed.

Tim Widden, forensic artist who has specialised in age progressions, said that he has created age progressions after a request from either the police or the Missing People charity. He does not create or publish them without the family’s consent.

“I normally ask for about 10 photos of the missing person that are as close as possible to the time they went missing. And then I'll also ask for photos of the immediate family, like parents and siblings, close in age to how old the missing person was when they went missing, and at the age the missing person would be now.

“You do get kind of family resemblance. For example, if a missing person particularly resemble one of their brothers or sisters or their mum or their dad, that can kind of help give you a steer into how they would have aged.

“What we call the cranial index, the kind of overall form of the head, there's a few different ones. And if you can see the whole family has got a similar one, that would indicate that probably the missing person would do too, and the collateral effects that then impact the face from that.”

Tim explained that he will also ask for contextual information about the person. This could include health conditions or lifestyle factors like dental problems or smoking.

“I've had them as well, where opticians have been involved, and the opticians have predicted the prescription the missing person would have now, and how that might affect how the eyes would look behind the glasses.

“I did one age progression, and I adjusted it because the person would have needed a strong prescription, which would have kind of magnified their eyes behind their glasses.”

He added that male faces change more with age due to the increased testosterone produced during puberty.

“I use Photoshop and stock image sites, and I'll look for facial features there in the ballpark of what I expect the missing person would have now. But then using Photoshop, you can really manipulate them how you want them. And when I say features, it’s not like you take a whole nose and make it bigger.

“You might take, the very top of the nose from one photo, the middle of the nose from another photo, the bump on the nose from another, and the nostrils from another photo.

“I composite them together like a collage, to build the nose that I think they'd have. And then you kind of stitch it all together to build up the face quite kind of slowly.”

Tim explained that it can be an emotional experience for the families. “From what I've been told, it's obviously difficult, particularly if you've got this image of someone in your head, and then you're presented with a new image.

“In a dream world, someone would recognise the age progression and then call it in to the police and tell them, hey, there's a guy lives down the road from me. He looks just like this photo, and it might be worth investigating. And that does work.”

While artificial intelligence has grown to create deepfake images and videos of people, Tim stated that it would not be used to produce age progressions like his. “Facial aging is so niche that there's just not the investment in it, because it's not got the profitability,” he said.

The media has evolved across time as a tool to help raise awareness of a missing person. It provides a platform that can easily reach the whole nation. Whether it is on Facebook, in a newspaper or on a television programme, it is a certain way for a case to get into the spotlight of the public eye.

Nick Ross, most familiar to viewers as the host of Crimewatch for over 23 years, urged the BBC to make appeals for missing people on the show. He was told that it would be unethical as people had a right to disappear.

“I found it very hard to make headway, and I was told if people wanted to disappear it was up to them.”

However, his idea was trialled and 15 years after the launch of Crimewatch, ‘The Search’ was launched in 1999 but aired for just one year.

While ‘The Search’ might have had the same social purpose as Crimewatch, it never measured the same in the number of viewers.

“There was no crime to solve. It was just, could you help find this person, so it didn't have that...What is the word that's used in drama? Jeopardy, it didn't have that sense of trying to be a home detective in quite the same way,” he said.

Nick argued that the national media can often treat a missing person as a story rather than an appeal. “Very often there won't even be a photograph of the person. Even though photographs are available, there won't be any description about where they might be.”

He also outlined the fact that women who are reported missing often grow to become bigger cases that are reported on by the mainstream media.

“Women as victims. It’s the old cliche about the woman or the girl being hunted and the terrible things happening to her, even though men are three times more likely to be murdered than women, that being the story that the media will go for is the classic.

“It's Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf, it’s sort of deepened human psyche,” he said.

Away from the world of television, other companies have also developed ways to help the searches of missing people.

Thameslink Railway collaborated with Missing People charity to have the faces of a missing person shown whenever a passenger logs onto the free train Wi-Fi.

Royal Mail has partnered with Missing People charity over the last decade to provide their own way of searching across the UK.

Matt Gower, head of environment, social and governance, said that they are provided with the description and photograph of a missing person every three to four weeks by the charity. He viewed the partnership as a no-brainer.

“We refer to our posties as 120,000 people up and down the country, in every community in the UK as sort of our own army, who walk billions of steps a day.

“When somebody is reported missing, and they may know roughly what areas they could be missing in, they need eyes and ears on the ground as fast as possible to locate the person.”

The charity has issued over 360 appeals to the postal service in the last 10 years.

“The information from the charity is then projected onto the handset of the posties in specific areas. It is available for the managers at the delivery offices to see as well and to maybe to guide the posties, or to have chats with them ahead of time," Matt said.

Matt explained that it has been important for postal workers to feel that they are doing more than just delivering letters and parcels. The partnership has allowed them to become active members of the communities they serve.

“And if it helps these families have been affected by disappearances? Then, all the better.”

At the heart of every searcher, no matter their method, is their commitment to finding missing people. Over 3000 people are reported missing in the UK every week. It has become a silent but ever-growing epidemic. However, the group of people who remain resilient are the searchers, as they continue in their pursuits of trying to find the missing.