At Eternity’s Gate: Was it an accurate portrayal of Vincent Van Gogh’s life?

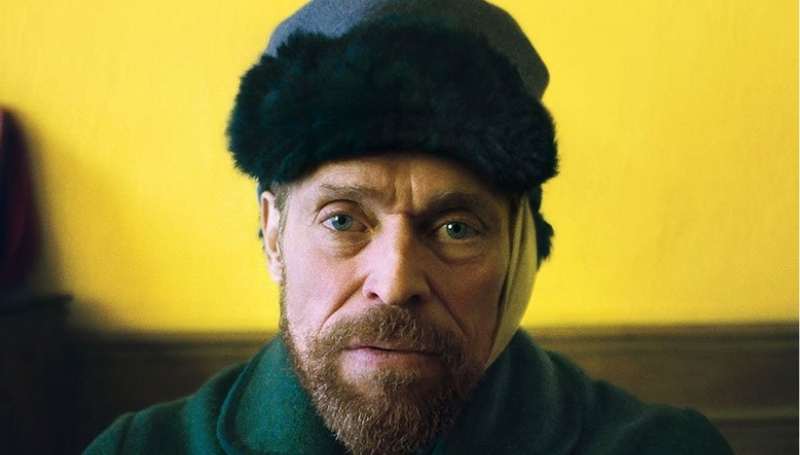

Willam Dafoe’s latest venture as Vincent Van Gogh sees a madman struggling with the medical ignorance of the times, but was it realistic? Our reporter Brittany Tijou-Smith discusses At Eternity’s Gate.

Rating: ★★★★

At a first glance, this biopic could easily be considered as avant-garde and artsy, but the techniques used to portray different concepts are easily identified as how the director effectively conveyed the emotional story of the melancholy artist, Vincent Van Gogh.

Willam Dafoe perfectly captures the turmoil and instability that someone living with mental illness in the late 19th century might have experienced.

After much criticism from artist friend, Paul Gaugin played by Oscar Isaac, that his paintings were like ‘clay’ and ‘unplanned’, as well as the news that he was leaving for Paris, Dafoe runs in a haze of unfocussed anger and fright. He then experiences the looping of past conversations, heightening the anxiety and overthinking process. Events like this alongside the bullying he experienced from locals and their children lead to Vincent’s eventual demise – from hacking off his ear to be given to Gaugin to get him to stay in the South of France.

Director, Julian Schnabel, decided to entertain a different theory of Van Gogh’s death, not seen in other works like Loving Vincent. This is that Vincent was quietly painting in a yard, when two boys ran through, one ‘dressed as Buffalo Bill’ and holding guns, used to shoot the painter once in the stomach. Afterwards he walks back to his room which seems miles away and says nothing about the boys until he dies.

The process is long and the content could have been condensed but it would have lessened the impact that the director was trying to make. At almost 2 hours long, Schnabel created a fairly realistic impression of Van Gogh’s life, however his madness is to be debated, as this film seems to over-exaggerate at some points. However it was never confirmed exactly what conditions Vincent had, due to the medical knowledge at the time and so some artistic licence is to be expected.

Read more of our reviews: