The homeless in Canterbury – a difficult story

The homeless are still spending their nights sleeping rough on the street, waking up to frozen leaves and their breath immediately condensing.

For many, this is because there’s no access to warm beds.

For many others, this is a choice.

Rough sleepers aren’t stupid. They know people will take pity on them if they are seen to be sleeping in the cold. Drunk students returning from clubs are known to be rather generous too, and so being up at three in the morning can prove to be rather lucrative.

Maybe, when walking past a homeless person, you’d consider buying them a sandwich, maybe even giving them a few pounds – but what if that were to go towards alcohol or drugs? No, it’s better to walk on.

I thought that rough sleepers had simple, albeit extremely tough, lives.

The prejudices that accompany our thoughts are rarely registered. In my case, I thought that rough sleepers had simple, albeit extremely tough, lives. It took spending some time with Catching Lives – an independent charity that aids the homeless and rough sleepers – to break down my preconceived ideas about homelessness. Their lives are no more simple than ours – and infinitely harder.

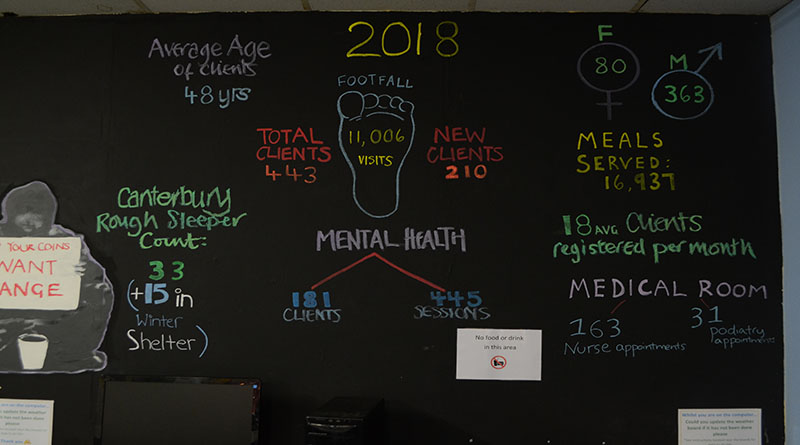

I’ll introduce James Duff: ex rough-sleeper-come-trustee of Catching Lives; it’s an independent charity focused on aiding homeless people in Canterbury and East Kent, with hundreds of clients a year. Here he is setting the scene for rough sleepers in the winter:

“Off the top of my head I would estimate we have about a client a month who dies and that to me is fairly average for how it’s been for the past five years.”

James said that his clients have physical issues which, when added to the cold, produce a deadly mixture. And yet, there are people who choose to stay out at night even when it’s coldest.

‘It’s been harder in the last few years.’

The average age at which homeless people die is 45 years old. Largely not from hunger. Hang around for long enough on Canterbury high street looking particularly disheveled, and somebody will buy a sandwich for you. But looking organically disheveled takes effort and sacrifice – and is one reason why people turn down warm beds.

If you are seen to be huddled in your bed sheets, sleepy-eyed and un-showered, you’ll appeal to people’s pity far more than if you’re clean and in fresh clothes after a good night’s sleep. Cultivating ‘the look’ and being seen living life on the street is vital, as I found out talking to a man named Lee. He’s been in and out of accommodation since he was 16.

‘It’s been harder in the last few years’ he said. I asked why, and he said that professional beggars give the ‘genuine homeless’ a bad look, and is another reason why he knows people stay out on the streets overnight – to come across as genuinely in need of charity. Lee fell homeless again six months ago, having been ejected out of temporary accommodation provided by the council. He was a chef, but because of his living standards he cannot pass health and safety checks to continue his work.

There’s an uglier side too. James laid out the various reasons for people not staying at Catching Lives’ night shelter. Some rough sleepers are racist, some are not sober enough, and some have social anxieties that inhibit them from staying. Many tried what the doctors prescribed, and their remedies were not effective. Being told this story countered another of my prejudices: that rough sleepers… well, they themselves must have done something to end up here, right?

Of course, I mean that gambling, drugs, alcohol, or some other antisocial behaviour brought them to the street. It’s not uncommon for addictions to lead their victims to a life without a home – but my viewpoint was dehumanising, wrong, and lacked all perspective. An addiction arises when the user needs to escape life, even if just for a moment. Yet, there’s an unending list of what turns people to drugs or alcohol: social anxiety, a health or family issue, a stressful job… I suspect the reason is an uncomfortable mix of many issues. James told me of one man who served in the army; he’d developed PTSD, which led to such severe night terrors he would scream and shout through the night – unless he’d drunk a bottle of whisky beforehand.

For people like this, a normal life may no longer be an option:

“We have clients who come in a couple of times a week, have something to eat, do their laundry and they’re not interested in anything else. Some of that have been doing that for years. And we will try and we will encourage them and tell them ‘If you want somewhere to live we can help you’ and that will probably change but it’s unusual people do that forever. No party’s going to solve homelessness anytime soon – and I don’t want to hark on about it, but I will – because we don’t have enough houses.”

I was told there are only six to seven thousand rough sleepers over the country, and that ending rough sleeping is a relatively doable pledge from the political parties. For instance: to end rough sleeping in Canterbury, around 45 beds would need to be sourced every night. This would need to be done in every town and city with a homeless population – but still, James reckons that’s reasonable with a bit of effort. But ending homelessness altogether would require serious change. And is also how my final prejudice was broken down.

The ‘hidden homeless’

I didn’t consider how people may be priced out of buying a house, break up with their partner, or lose a family member they were dependent on. These are all reasons people become homeless, yet are totally out of one’s control – they are simply victims of circumstance, something I’d never considered. But being homeless doesn’t necessarily mean out on the street. The hidden homeless are people living in temporary housing, on their parents’ or a friend’s floor, or in poor conditions. So now, with this classification, 84,000 families are homeless in the UK. And that’s much harder to deal with.

James made an obvious yet valid point – if there are enough affordable houses for everyone, we wouldn’t have any homeless people. It’s becoming increasingly harder for people to buy houses, which could help explain the 77% increase in people in temporary housing since 2010. Any changes made would have to be done in equal amounts all over the country. Canterbury City Council can’t start building more affordable housing or offering more support for the homeless without the support of other towns – people would flock here, solving nothing. Only significant funding into affordable housing will ever truly end homelessness. So, with all that in mind, what can us passers-by do?

Donate. To charities like Catching Lives, to the homeless directly. Charities do such amazing work in keeping people away from antisocial habits and creating an actual community; they encourage their clients to have hobbies, to move into affordable housing, to really get their lives back on track. This might seem like a rather long-winded tale which actually takes you right back to where you started. But next time you think about giving money, put yourself in the receiver’s shoes. Your life suddenly looks bleak. You’re cold. You’re tired. You rely on the charity of others to feed and clothe yourself.

Donate.

To charities if you want to know what your money is going towards. To the homeless you pass. Or don’t – but if you wish to show support, maybe write to your MP. Homelessness is inhumane, and is an issue everybody should want solved.