What is Coercive Control?

Women’s Aid CEO, Katie Goshe, says that “coercive control lies at the heart of domestic abuse.”

Yet, it was revealed in a police watchdog report on the police response to domestic abuse that “some officers still do not understand the dynamics of domestic abuse and coercive control.”

If some police officers don’t understand the dynamics of domestic abuse and coercive control, then how are the public meant to understand it?

Many listeners of BBC Radio 4’s “The Archers” only learnt about the domestic abuse form, coercive control, through it’s two and a half year long story line.

The story saw ‘Rob’ coercively control his wife, ‘Helen’.

But here you will find out what coercive control is, what the patterns of behaviour are, what the sentencing is like and where you can find help.

What is coercive control?

The term was first introduced by Professor Evan Stark, a forensic social worker, who published a book on the form of abuse in 2007.

The concept of coercive control is where an abuser, male or female, isolates, intimidates, undermines, exploits and deprives a victim continuously.

It’s a purposeful pattern of behaviour.

The Government definition of domestic violence and abuse outlines controlling or coercive behaviour as:

Controlling behaviour: a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour.

Coercive behaviour: a continuing act or pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim.

Women’s Aid have said that being coercively controlled is like having “invisible chains” and Professor Evan Stark likened coercive control to being taken hostage.

What are the patterns of behaviour of an abuser?

Sometimes coercive control is hard to recognise. For example, when an abuser monitors ones movements it can be mistaken as being caring, and concerned for their safety. But if you’re repeatedly being rung and messaged asking where you are, who you’re taking to when you’re at your place of work maybe alarm bells should start ringing…

Here’s a few examples of behaviour to look out for:

- Isolating you from friends and family

- Depriving you of basic needs, such as food

- Monitoring your time

- Monitoring you via online communication tools or spyware

- Taking control over aspects of your everyday life, such as where you can go, who you can see, what you can wear and when you can sleep

- Depriving you access to support services, such as medical services

- Repeatedly putting you down, such as saying you’re worthless

- Humiliating, degrading or dehumanising you

- Controlling your finances

- Making threats or intimidating you

Examples courtesy of Women’s Aid.

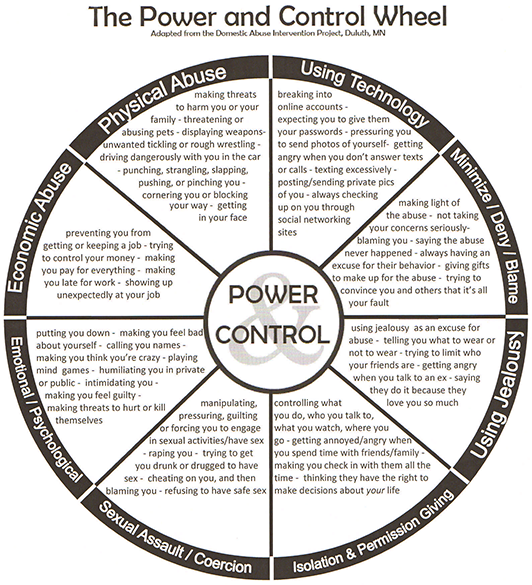

Another great tool to spot patterns of an abuser’s behaviour is the power and control chart:

What constituents an offence?

Under 76 of the Serious Crime Act 2015 there are four checks to satisfy for the offence to apply;

- To qualify as an offence in the eyes of the law, the coercive behaviour has to to take place repeatedly over a period of time rather than a couple pf isolated incidents. But there is no set number of incidents that have to qualify.

If the victim has been forced to change their way of living, for example changing their job to suit the abuser, this would satisfy for the offence also. - The coercive behaviour from the abuser has to have a “serious effect” on the victim.

The victim has to show that they are caused to feel fear and that violence will be used against them. Or, the victim has to prove they are caused serious alarm/ distress which has an effect on their day to day lives. - The abuser must know, or ought to know, that their behaviour will have a serious effect on their victim

- The victim and abuser have to be ‘personally connected’, when the incidents took place.

‘Personally connected’ can mean in an intimate personal relationship (living together or not), or a family members living together or having been in a previously intimate personal relationship.

The victim and abuser don’t have to be still living with one another, or in a relationship when the incidents are reported – just as long as they were ‘personally connected’ when the abuse took place and when the offence came into law.

What is the sentencing of an abuser?

Since December 2015 coercive or controlling behaviour has been a criminal offence.

The then Minister for Preventing Abuse and Exploitation Karen Bradley said,

“No one should live in fear of domestic abuse. Our new coercive or controlling behaviour offence will protect victims who would otherwise be subjected to sustained patterns of abuse that can lead to total control of their lives by the perpetrator. ”

So what can an offender expect?

The offence will carry a maximum of 5 years’ imprisonment, a fine or both.

Where can I get help?

Women’s Aid

Women’s Aid is the UK’s national women’s federation to end domestic abuse against women and children.

ManKind Initiative

ManKind Initiative was the first charity in the UK to support male victims of domestic abuse.

Their aim is “to ensure all male victims of domestic abuse (and their children) are supported to enable them to escape from the situation they are in. ”

Their anonymous helpline is: 01823 334244

Rising Sun

Rising sun is a Domestic Violence and Abuse charity based in Canterbury, Kent.

Their crisis line is: 01227 452852